Novacon is an annual convention run by the Birmingham SF Group, which takes place over the first weekend of November. The last one I attended was Novacon 27 in 1997. Ten years ago. Back in those days I would go to two or more cons a year - typically the Eastercon and Novacon. When I moved to the Middle East, I could only return to the UK for a single con each year - and chose the Eastercon, on the entirely sensible grounds that more of my friends would be at it. After returning to live in the UK, I didn't bother with any conventions for a couple of years... until the 2005 Worldcon in Glasgow. And since then, I've been happy with just one convention a year, the Eastercon.

But, for some reason, I decided this year to also attend Novacon. Which this year took place in Willenhall.

Travel problems soured my visit to Fantasycon, and that was only a 40-mile train journey. This time I was travelling around 100 miles - and I'd have to change trains at Birmingham New Street. Foolishly, I'd thought that earlier screwed-up trip was just a one-off. But it seems the British rail network imploded some time during the past couple of months. My train to Walsall was delayed by thirty minutes - in fact, only local trains were actually running on time. As it was, I still managed to arrive in Walsall at the correct time. Fortuitous connections at Birmingham New Street, I think.

The hotel where Novacon 37 was taking place proved to be one of those low flat modern ones, situated just off a motorway junction. The rooms were laid out along a corridor which mapped out a square. The entrance to this square was at one corner. Naturally, I was given the room furthest away, on the corner diagonally opposite. After dumping my bag, I headed for the bar...

If this year's Eastercon in Chester felt like a two-day convention stretched out over three days, then Novacon felt as though it were exactly the right length. I chatted with various people on the first night - including Guest of Honour Charles Stross - before attending the Opening Ceremony. Later that evening, they brought out the free wine, free books and free food for some book launches and signings. I don't actually recall what was being launched, or who was signing. I do vaguely remember deciding I'd had enough and staggering off to my room around midnight. The next day I was told I'd actually left at ten o'clock.

- before attending the Opening Ceremony. Later that evening, they brought out the free wine, free books and free food for some book launches and signings. I don't actually recall what was being launched, or who was signing. I do vaguely remember deciding I'd had enough and staggering off to my room around midnight. The next day I was told I'd actually left at ten o'clock.

As usual, I was up early the next morning. Unsurprisingly, I had a bit of a hangover. Breakfast wasn't bad - although the Quality Hotel keeps their plates dangerously hot. You can't hold one unless you wrap a dozen paper napkins around your hand. I spent the day in the bar, but I no longer recall the topics of conversation. At four o'clock, Andy Remic gave a reading from his new novel, War Machine , published by Solaris. He stood with his back to a window, and through the window I could see an expanse of grass and at its far edge some twenty metres way a line of trees. Every now and again, a pair of squirrels would leap across a gap in the trees - and only just make it. One squirrel, in fact, missed completely, and only saved itself from plummetting to the ground by grabbing the other squirrel's tail. It was a little distracting. Andy's book, incidentally, is militaristic sf, and if the excerpt he read is any indication it should be a good read.

, published by Solaris. He stood with his back to a window, and through the window I could see an expanse of grass and at its far edge some twenty metres way a line of trees. Every now and again, a pair of squirrels would leap across a gap in the trees - and only just make it. One squirrel, in fact, missed completely, and only saved itself from plummetting to the ground by grabbing the other squirrel's tail. It was a little distracting. Andy's book, incidentally, is militaristic sf, and if the excerpt he read is any indication it should be a good read.

Around half past seven, a gang of eleven of us went out for a curry. This entailed a ten-minute drive in two taxis. The food wasn't bad - although a couple of those present disagreed. Back at the hotel, we sat around, drank a bit more and generally complained about how knackered we were. I lasted until midnight before going to bed.

On the Sunday, I attended my second programme item of the con. Which makes Novacon 37 something of a record-breaker for me. I typically spend cons in the bar, only attending book launches, author readings, or awards ceremonies. But this time, I actually sat through a full sixty-minute panel discussion. The topic was 'The New Optimism in British Science Fiction'. The panel comprised Eric Brown, Ian Watson, moderator Catherine Pickersgill, GoH Charles Stross and Andy Remic. An interesting discussion, although I don't recall any real conclusion being reached.

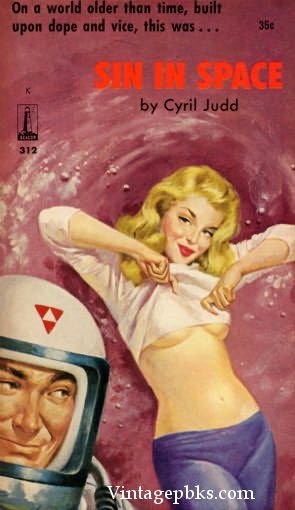

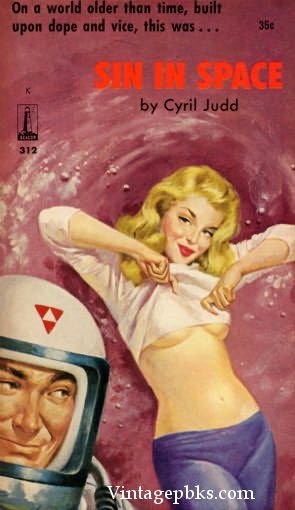

Throughout the weekend, I went for occasional wanders about the dealers' room. Which was surprisingly big for such a small con. Among the 17 books I bought were Outpost Mars by Cyril Judd, and its "spiced up" Beacon Books version, Sin in Space (see here for my comments on the Beacon Books version of AE van Vogt's Undercover Aliens

Throughout the weekend, I went for occasional wanders about the dealers' room. Which was surprisingly big for such a small con. Among the 17 books I bought were Outpost Mars by Cyril Judd, and its "spiced up" Beacon Books version, Sin in Space (see here for my comments on the Beacon Books version of AE van Vogt's Undercover Aliens ; I plan to do the same for Sin in Space). Most of the others were obscure paperbacks, bought for a couple of quid, by the likes of Colin Kapp

; I plan to do the same for Sin in Space). Most of the others were obscure paperbacks, bought for a couple of quid, by the likes of Colin Kapp , David J Lake, Rudy Rucker

, David J Lake, Rudy Rucker , Lin Carter

, Lin Carter , and Barry N Malzberg

, and Barry N Malzberg . I also picked up copies of Time Pieces and disLocations, short story collections edited by Ian Whates. And Andy Remic's Quake

. I also picked up copies of Time Pieces and disLocations, short story collections edited by Ian Whates. And Andy Remic's Quake and Warhead

and Warhead , both of which he signed for me.

, both of which he signed for me.

Since Eric Brown and myself were both heading north, we decided to travel together. Tony Ballantyne dropped us off at Walsall station at 3 o'clock (thanks for the copy of Divergence , Tony). I didn't arrive back home until 7:30. The train from New Street was packed solid, and forced to take two diversions because of work being done on the lines. In the old days, you could blame a single company - British Rail - for screwing up your journey. Now it's the fault of half a dozen. Privatising British Rail was a stupid thing to do.

, Tony). I didn't arrive back home until 7:30. The train from New Street was packed solid, and forced to take two diversions because of work being done on the lines. In the old days, you could blame a single company - British Rail - for screwing up your journey. Now it's the fault of half a dozen. Privatising British Rail was a stupid thing to do.

On the whole, an enjoyable con. I got to meet up with friends, and meet new people. I didn't spend as much in the dealers' room as I'd expected or feared. Which is good. I did spot a couple of first editions I wanted, but I managed to resist temptation. I don't remember every thing that happened during the weekend, but I do recall - chatting with Ian Whates about prog rock (and letting Tony Ballantyne listen to some Tinariwen on my Yeep

on my Yeep ; he liked it more than the death metal...); discussing the current craze for zombies with Mark Newton and Christian Dunn; watching someone hand Charles Stross all twelve of his novels to sign, and his earlier book on Web architecture; talking about writing with Andy Remic; listening to Ian Watson's many funny anecdotes; being very surprised to see Liam Proven up and about before noon... Anyway, here are a few photos I took during the weekend.

; he liked it more than the death metal...); discussing the current craze for zombies with Mark Newton and Christian Dunn; watching someone hand Charles Stross all twelve of his novels to sign, and his earlier book on Web architecture; talking about writing with Andy Remic; listening to Ian Watson's many funny anecdotes; being very surprised to see Liam Proven up and about before noon... Anyway, here are a few photos I took during the weekend.

It was a fun convention. I might even go again next year. I'll certainly not wait ten years before my next Novacon...